Grunge, Kate Moss, and the Industry That Lost Its Mind Over Both

Sometimes fashion shifts arrive slowly, like a turning tide. Other times they come crashing down like a brick through a boutique window. The early '90s did the latter. One moment fashion was all about polished glamour, high gloss supermodels, power shoulders, and the kind of hairspray levels that the EPA would fine nowadays. The next, someone handed the industry a cigarette, a thrifted cardigan, and a bucket of emotional detachment and said, “Here, this is the new normal.”

Grunge, as grunge does, did not walk in politely. It kicked the door down, rolled its eyes at whatever happened to be on the mannequins, and rewrote the dress code with a Sharpie in one hand and a spray can in the other. And right at the center of said cultural whiplash stood a 5'7" teenager with crooked teeth, knocked knees, messy hair, and a body the fashion establishment took one look at in person and insisted was wrong. On camera however, the story was different.

Kate Moss didn't just enter the industry, she dominated it.

But to understand how seismic that was, it helps to remember what fashion looked like before the tremor hit. And why the public had such a massive meltdown loud enough to reach the White House.

In the late '80s and early '90s, fashion really only projected one consistent message. Things had to be bigger, glossier, shiner, and of course, richer. Preferably wearing a Versace minidress. Supermodels were the superhero archetype of beauty. Cindy, Naomi, Linda, Claudia. Polished and perfected to an aerodynamic sheen, built like statues, and styled to the nines like luxury was their natural habitat.

Designers worshipped glamour with near religious intensity. Every silhouette perfectly controlled, every photo aspirational, every model eight feet tall and built like Greek goddesses who had just signed their next perfume deal.

Up until Kate Moss of course.

She wasn't sculpted, or polished, or like she'd spent three hours being misted with Evian and Ichor backstage. She looked real. Like she lived in a real bedroom, like she led a real life, like she had real hobbies. She even looked like she actually slept once in a while.

The industry had never really seen anything quite like her, and the public was wholly unprepared.

When Corinne Day photographed Moss in her messy London flat, with her neon underwear, loose ponytail, and teenage bedroom energy, the fashion world finally saw what London's underground had been seeing for years. The anti-supermodel. A counter-image. A complete rejection of the "perfect woman" that ads had been trying to sell.

It wasn't glamorous or glossy. It was raw, lived in, and almost painfully normal. Everything the industry despised. It was "grunge". To the fashion insiders living on a diet or rebellion, cigarettes, and club night inspiration, it was electrifying.

To the rest of the world? It was an international crisis.

Newspapers demanded the industry explain "that skinny girl." Parents blamed Moss for their daughters' eating disorders. Politicians made speeches. The phrase "heroin chic" got pinned to her chest with the kind of misplaced moral panic usually reserved for Satanic rituals and crop tops in church.

The funny thing is, Moss wasn’t “doing” anything. She wasn’t trying to collapse an industry standard or usher in a wave of such normcore minimalism. She was just existing, looking the way she’d always looked, wearing whatever her friends stitched together or found in a thrift bin. And yet, existence can be revolutionary when the standard has been unnatural for too long.

The world needed someone to blame. Targets to point at and yell "it's all their fault!" And everyone knows it’s always easier to blame a teenage girl than the system that groomed the problem.

What’s wild is how loudly the political class weighed in. The Clinton administration publicly condemned the aesthetic, folding Moss’s face into a moral panic campaign about drug culture, as if she, personally, had been distributing heroin in micro-doses via Calvin Klein ads.

The whole ordeal exposed something the industry already knew: fashion likes rebellion, but only when it fits neatly inside an ad campaign and doesn’t make anyone uncomfortable.

Grunge wasn’t designed for comfort. It was designed to disrupt. Kate Moss didn’t just change what models looked like. She changed who controlled the narrative.

Supermodels used to be inaccessible icons. Moss felt like someone you might see in a record store or sitting on the curb outside a club with a cigarette and an old ratty coat. That familiarity broke fashion’s hierarchy. Suddenly, the industry wasn’t dictating beauty from a marble pedestal anymore, it was looking at youth culture and trying to catch up.

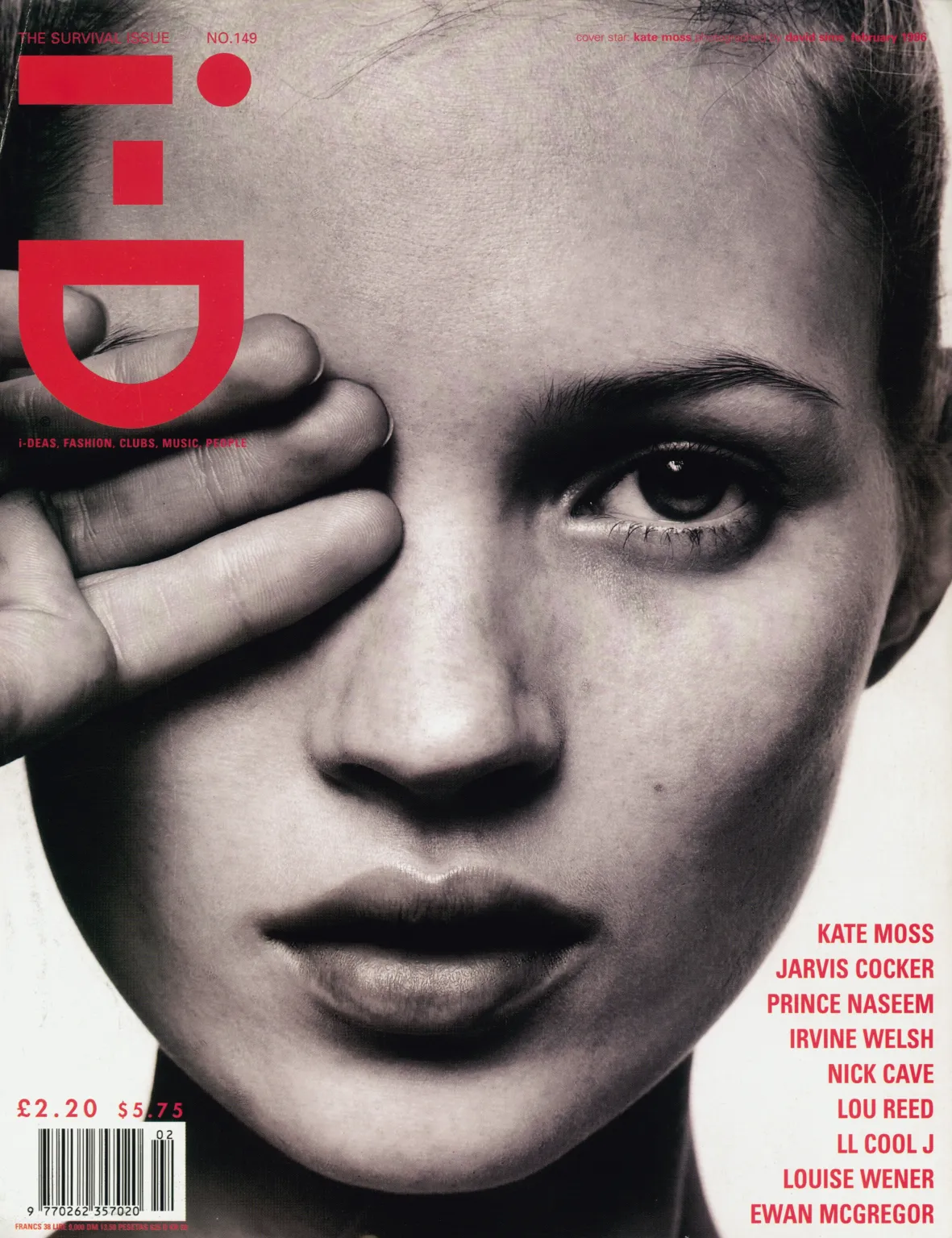

London became the global center of “cool.” Designers like McQueen and Chalayan were redefining runway language. Photographers were working out of bedrooms and reinventing editorial photography. And magazines like i-D were proving that the next wave of fashion didn’t need a million-dollar budget.

It needed vision. And so grunge wasn’t just a trend. It was a reordering of power.

While the rest of the world had still been fixated on glamour, London had been quietly (or rather, loudly) building something feral and new. The city's creative scene, the clubs, the bedsits, the art students, the photographers, the no budget magazines held together with spit and a vision, lived in chaos. And they wore it proudly.

Edward Enninful, fresh out his teenage years and working at i-D, called it rebellion. It wasn’t fashion that needed a runway, it was fashion that needed a basement gig, a night bus, and a cigarette break outside a club at 3 a.m. Fashion that craved the streets.

Grunge wasn’t imported neatly from Seattle. In London, it wasn’t even specifically grunge, it was just young people refusing to dress "correctly". Flannel over florals. Slip dresses with ladders in the tights. Doc Martens with everything. Clothes that looked like they’d been found on your floor instead of arranged on a hanger.

i-D understood it. The Face understood it. Underground photographers understood it.

And eventually, Vogue had no choice but to understand it too.

For a long time, the word “commercial” was like a slur, only used in magazines like i-D. Vogue, on the other hand, was the cathedral of fashion. It was polished, elegant, expensive. Not messy. Not rebellious. Definitely not wearing a ripped flannel shirt over a floral Ralph Lauren dress.

That is, until, it was of course. Because culture doesn’t ask for permission.

Grace Coddington, recognizing the shift, decided Vogue needed to stop pretending nothing was happening. Without telling Anna Wintour the full plan (because she knew better), she put together what would become one of the most famous editorial shoots in fashion history: the Vogue grunge story.

Boots, flannel, unbrushed hair, mismatched layers. Thrown together, but styled with Vogue’s precision and photographed with Meisel’s eye. It was the collision of glamour and grime, and it produced images that practically hummed with cultural tension. The establishment didn’t know whether to applaud or faint. But the youth did. They finally saw themselves on a page that had never acknowledged them before.

When Vogue printed grunge, the rebellion became real.

Of course, designers like Marc Jacobs weren’t going to go dipping a toe into grunge. No, no, no. That would be crazy!

It didn’t matter. He’d already made his point. He knew he wasn’t designing clothes for Park Avenue. He was designing clothes that felt like the era. Clothes that didn’t posture. Clothes that had personality instead of perfection. The collection was sloppy in the most intentional way. Knits piled over flannels. Bias cut dresses over thermals. Chopped hems. Messy layers. And the confidence needed to turn their backs to the industry and say, “This is fashion whether you like it or not.”

While the younger designers were welcoming grunge, the establishment reacted as if someone had released a raccoon into the front row. The old guard didn’t just dislike it, they recoiled entirely. Wintour was expectantly dismayed, calling the look unfashionable, unflattering, and generally beneath Vogue’s glossy standards. Carlyne Cerf-de-Dudzeele practically went feral, insisting she “hated grunge,” muttering about big boots and “poverty looks” like the style was personally offending her sensibilities.

And Perry Ellis? They didn’t just wrinkle their noses, no, they fired Marc Jacobs over his grunge collection. One show packed with layered thermals, shredded dresses, and combat boots, and suddenly he went from rising star to corporate liability. The irony is that Jacobs hadn’t misread the room at all. He’d simply read a different room.

Outside the boardrooms and the couture salons, the underground loved it. For the club kids, the students, the basement photographers, the people actually living the decade instead of editing it, grunge wasn’t a crisis. It was the first time fashion looked like them. Designers were feeding off that energy, embracing the rawness and chaos like it was the antidote to decades of overproduced glamour. They were drinking the new Kool-Aid.

What the establishment read as decline, the youth saw as honesty. And what the gatekeepers dismissed as “sloppy,” “unrefined,” or “unprofessional,” designers recognised as a new visual language. The problem wasn’t that grunge looked wrong, it’s that it looked real. After years of aspirational fantasy, authenticity felt dangerous. Fashion wasn’t used to seeing the world without its makeup on. It's ironic, because what the fashion public and publications mistook for a dangerous new ideal was actually a return to something closer to reality. Human bodies. Human clothes. Human expressions. Fashion had been selling a fantasy for so long that authenticity looked like a threat.

People hated the look because they refused to see what it represented. The reality, imperfection, and naturalism of a generation exhausted by glamour. The beauty of grunge wasn’t that it looked “effortless.” per se. It was that it looked human. Clothes weren’t pretending anymore, and bodies weren’t pretending either.

Designers saw that as an opportunity. The public saw it as a threat. But culture doesn’t stay still just because someone in pearls says it should.

After the backlash, fashion didn’t stay grungy forever. It never does of course. Trends mutate, evolve, eat each other alive. But the grunge moment left a scar. A permanent reminder that beauty norms can fall apart overnight if someone brave enough walks into the frame.

Kate Moss wasn’t the industry’s downfall. She was its wake up call. Grunge wasn’t the decline of taste. It was the decline of pretense. The public hated it. Designers loved it. But the truth sits between the two.

Grunge made fashion honest.

Messy honest.

Uncomfortable honest.

Necessary honest.

And fashion has never been the same since.

Citations & Sources

Baker, P. (1997, May 21). Clinton blasts “glorification of heroin” in magazine fashion photo spreads The Washington Post. www.washingtonpost.com/…

Borrelli-Persson, L. (2020, November 7). Galliano. McQueen. Chalayan. McCartney. these london libertines “created their own rules.” Vogue. www.vogue.com/…

Cartner-Morley, J. (2024, September 11). Back to the 90s! the TV show giving a front row seat to fashion’s hard-partying superstars. The Guardian. www.theguardian.com/…

Freeman, L. (2018, September 27). “we were just boyfriend and girlfriend taking pictures”: Mario Sorrenti on Kate Moss. British Vogue. www.vogue.co.uk/…

Hulu. (2024, September 13). All Change at Vogue. In Vogue: The 90s. episode.

Hulu. (2024, September 13). The Fashion Rebels. In Vogue: The 90s. episode.

Jaculewicz, D. (2025, January 24). The Perry Ellis Runway show that got Marc Jacobs fired - grunge, Spring/Summer 1993. L’Officiel USA. www.lofficielusa.com/…

McFall, marni. rose. (2023, September 15). Flannels thinks: An ode to the O.G. supers. Flannels. www.flannels.com/…

O’Hagan, S. (2010, September 4). Corinne Day: she added grit to the glamour of fashion photography. The Guardian. www.theguardian.com/…

Poneman, J., & Coddington, G. (1992, December). Grunge & glory. Vogue, (19921201), 254–263.

Ramzi, L. (2024, May 31). A 1990s fashion history lesson: Supermodels, grunge, and the dawn of the Digital age. Vogue. www.vogue.com/…

Renata. (2025, March 7). Why can’t I get over that photo of Kate Moss by Corinne Day for British Vogue’s June 1993 issue? Untouchable. www.untouchableblog.com/…

Rodgers, D. (2023, August 14). 5 lessons in authentic ’90s glamour from the original supermodels. British Vogue. www.vogue.co.uk/…

Walker, H. (2024, September 10). What we learn about Anna Wintour from in vogue: The 90s. The Times & The Sunday Times. www.thetimes.com/…

Yaeger, L. (2015, August 31). Slammed then, celebrated now, Marc Jacobs’s Perry Ellis Grunge Show was a collection before its time. Vogue. www.vogue.com/…