Exclusionary Inclusivity and The Return of The 2000s

There are a few phrases that look nice in pastel fonts. "Size inclusive." "For every body." "Diversity Forward." These words get plastered all over campaign posters, TikTok captions, and brand mission statements that sound like self help quotes. And yet, behind the polished photos and faux sincerity, the same problem lingers. Most of women's fashion isn't built for most women.

The industry loves talking on and on about inclusivity, but it rarely practices what it preaches in a way that truly matters. Diversity and inclusivity have just become another buzzword. A soft, marketable idea that sells guilt free shopping to people who just want to feel seen. Every few years fashion promises change. And every few years it all just rebrands the same exclusivity with a new tone of voice and the same old styles.

For a start, it's all but common knowledge that women's clothing sizes are fiction.

A "size 0" in one brand can fit like a "size 6" in another, while a "large" somewhere else could fit smaller than a "medium". The system doesn't exist to help women find clothes that fit, it exists to manipulate how they feel about themselves when they put them on. The confusion isn't accidental either. Brands like Abercrombie & Fitch once openly admitted that they didn't want certain body types in their clothes.

In a 2006 interview, then-CEO Mike Jeffries had said that the brand was made "for the cool kids," and that "a lot of people don't belong (in our clothes), and they can't belong. Are we exclusionary? Absolutely", and that plus-size customers simply weren't part of that image.

Vanity sizing, or the quiet inflation of numbers to flatter consumers, has completely distorted what sizes mean. Decades ago a size 8 was considered small. Now it's a mid-range, sometimes even "curvy". Designers made the numbers smaller so women could buy clothes that said "4" instead of "8", as if self-worth could shrink with a label.

It's a cruel psychological trick that feeds the beauty standard while pretending to empower it. "You're not bigger," it says. "The number just changed." And it works, at least in sales terms. But for anyone outside the narrow body range these systems were designed around, particularly petite or plus-size shoppers, it turns finding clothes into a maze.

Small women often end up swimming in unflattering garments labelled their size, while plus-size women face a completely different problem. Their size often doesn't exist at all. It's not "out of stock". It was never even made in the first place.

Mainstream brands have learned to say the right things. "Inclusive sizing" gets printed in big bold text and slapped on websites and ad campaigns, followed by a new size chart that extends to maybe a 3X, sometimes 4X, if they're feeling particularly generous. It looks progressive, but it's not equality. It's a marketing strategy.

Luxury fashion is even slower to adapt. The so-called "heritage" houses, the ones that built their reputations on exclusivity, treat inclusivity like a novelty, or a risk. They'll show one plus-size model on a runway once a season, photograph them in perfect lighting, edit and cut and crop the photo to high hell, and call it representation. But the clothing? Still sample size. The racks? Still stop at 12. The luxury industry has always a long history of making it s standards explicit. Dolce & Gabbana once marketed “thin and gorgeous” sneakers, and when criticised, responded to fans online with messages like “darling you prefer to be fat and full of cholesterol??? I think u have a problem,” and “u think is better to be fat full of hamburger??? stupid.” Inclusivity is the current aesthetic, not a structural change. It's a look. Something to post, not something to build around. The word "inclusive" doesn't mean what it used to. It's been flattened into a tagline. Something soft and neutral and easy to print on a cute little tote bag that gets sold for 500 dollars a pop. Fashion, like beauty, has figured out that pretending to care about representation is more profitable than actually participating in it.

Even when brands finally do court larger customers, it’s often a token effort or a marketing gimmick. Plus-size capsule collections, single runway shows, one-off ads get buzz for a week. All new and shiny and pretty, but rarely leading to lasting change. Along with this, there have been many a time where brands have made their plus size fashion “inclusion” the butt of a joke, whether intentional or not.

This mockery has never faded with time either, being evident even as recently as 2019, when fast fashion giant Forever 21 included Atkins diet bars in shipments of plus-size clothes. This "perk" was perceived as blatant body-shaming and many plus-size customers complained that receiving diet snacks with their order was hurtful. F21 quickly apologized, calling it an “oversight” in their promotion, but the damage was done.

By @MissGirlGames on Twitter

The beauty industry runs the same playbook. When a makeup launches "50 new inclusive shades", that usually means forty five of them are different shades of the "flesh" crayon, four are vaguely tan, and one looks like a leftover Halloween paint labelled "espresso".

That's not inclusivity. That's pretending the problem is solved.

When everything is called inclusive, the word stops meaning anything. It becomes a cover for a system that still prioritises aesthetics over accessibility. Brands don't actually have to be diverse, they just have to sound like they are. The fashion industry has truly mastered this. Polishing exclusion until it looks like empowerment.

Even when inclusivity exists, it's often paywalled. Athleisure brands like Lululemon and Alo Yoga talk endlessly about empowerment through activity, comfort, and wellness. Their ads are all about freedom and flow and confidence, usually illustrated by super-fit women doing yoga on cliffs in 150 dollar leggings they will never wear again.

It's marketed as a lifestyle, not clothing, but it's a lifestyle built on cost. A pair of leggings should not cost half a paycheque. The irony is that "comfort", something that should be universal, has been turned into a luxury product. If comfort and movement are only accessible through designer sportswear, then empowerment isn't the message. It's just the branding.

By Bloomberg/Getty Images

For all the progress fashion claims to have made, it still can't decide what bodies it's actually for. The industry claims that there's been a clear shift away from the ultra-thin archetype that defined the early 2000's runways, but the industry's pendulum swing isn't as radical as it looks. Today's "acceptable" body is still curated. Flat stomachs, visible curves, and an overall shape that's only considered "inclusive" because it's a new flavour of impossible to achieve.

When Y2K aesthetics came back, so did the low-rise jeans, the cropped and cinched baby tees, and the very specific type of body they were designed for. Social media might say "all bodies are in" but the clothes still disagree.

The cultural judgement hasn't disappeared either. Fatphobia has just gotten more subtle. It hides behind "health" discourse, or "fitspo" content, or "style just doesn't flatter everyone". There's always a polite way to say that certain bodies still don't belong in certain clothes.

And that's the part of fashion that inclusivity slogans never touch. The unspoken hierarchy that rewards thinness and symmetry, no matter how many size ranges a brand offers.

Inclusivity right now functions more like a performance than a principle. Brands create moments. Runway appearances, capsule collections, or a single ad campaign that gets shared for a week, and then quietly move on.

There's rarely a follow-through. There's rarely infrastructure put in place to make that inclusivity permanent. And that's because the fashion industry has never really wanted to alienate the exclusivity it was built on in the first place.

Inclusivity and exclusivity can’t coexist in the same space. Still, brands try to have it both ways. To appear progressive without actually changing their audience. It's not about actually including more people, it's about appearing to.

By Unknown/Versace Milan SS2010

It's also worth noting that inclusivity like this costs money. Expanding size ranges means new patterns, new materials, more storage, more models, and more marketing. For smaller labels, that's a genuine challenge. For global corporations, it's a choice they've decided isn't worth the investment. So instead, they perform inclusivity. The cheaper alternative.

The early 2000s are back. Not just in clothes but in attitude. The same low-rise silhouettes, the same tabloid culture, the same quiet expectation for women to fit a specific aesthetic in order to be desirable.

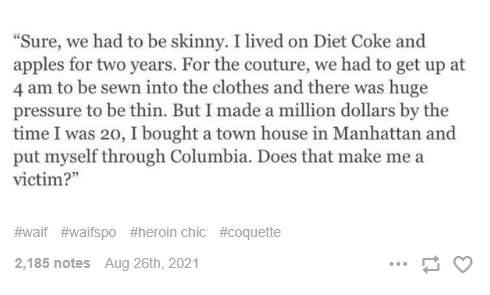

The difference now is that it's dressed up in irony. People wear it like nostalgia, but the messaging hasn't aged at all. What was once called "heroin chic" now gets rebranded as "Pilates princess" or "waif" and further into "coquette" as a whole. What used to be diet culture now appears under "wellness". What used to be unhealthy obsession and idealisation of unhealthy bodies is painted as "manifestation". The words change, the policing of bodies does not. And with the return of the 2000's skinny goal and aestheticising eating disorders again, this fatphobia sometimes isn't even bothered to be hidden anymore. As of the time of the writing of this blog, just days ago a designer openly and proudly refused to make plus sizes all together. In a TikTok she told viewers, “you just need to choose health and drop to a safe size,” claiming brands don’t need to stock anything above a certain size. Even after being accused of being blatantly fatphobic, she, rather than apologising for her statements, instead decided to double down, stating that she believed “not all brands need to be ‘inclusive’…Being inclusive isn’t what I’m trying to be” By Marie Efstratiou/Tiktok

Y2K fashion was built on scarcity. Of fabric, of forgiveness, and of body types. Bringing it back without rethinking it just resets the clock. The same insecurities, the same impossible ideals, just wrapped in modern lighting, an Instagram filter, and a bright pink bow that says "inclusive."

True inclusivity in fashion would mean designing clothes around bodies, not against them. It would mean consistent sizing that works across brands. It would mean affordability that isn’t conditional on thinness or wealth. It would mean representation that lasts longer than a marketing quarter.

It would also mean stopping the constant moral posturing. Inclusivity doesn’t need to be branded. It doesn’t need to be hashtagged or advertised as an act of charity. It should be the default, not the selling point. Inclusivity can’t exist if it only shows up in marketing. It can’t exist when comfort is a luxury, when sizing is psychological warfare, or when the only acceptable diversity is the kind that still looks good in campaign lighting.

Until that happens, the word will keep being printed, posted, and sold. Another label, another buzzword, another reason to buy. And once again, the people it claims to represent will still be left searching for something that fits. Fashion has always been a mirror. Reflecting who society wants to see, and who it doesn’t. As of right now, that mirror is distorted, curved by profit, nostalgia, and selective empathy.

It's strange how easily fashion forgets what it once punished. The industry isn’t short on creativity. It’s short on honesty.The truth is simple: fashion is inclusive when it stops needing to say it is.

By Deactivated Tumblr User/Abbey Lee Kershaw

- Bourne, L. (2017, June). Size 8 Shopper Calls for H&M to Change How It Sizes Its Clothing In Viral Facebook Post. Glamour. www.glamour.com/…

- CBS LA. (2013, May 9). Abercrombie & Fitch CEO’s Alleged Comments About “Larger” Shoppers Strike An Angry Chord With Women. Cbsnews.com. www.cbsnews.com/…

- Chan, S. (2023, April 29). Dolce & Gabbana’s new “Thin & gorgeous” sneakers cause online outrage. The Hollywood Reporter. www.hollywoodreporter.com/…

Forever 21 issues apology after plus-size customers receive diet bars inside of packages. (2019, July 24). ABC7 New York. www.abc7ny.com/…

Committing to a world of good. Etsy. (n.d.). www.etsy.com/impact

- Gen Zers and millennials are making climate-conscious buying decisions - marketing charts. Marketing Charts. (2024, June 7). www.marketingcharts.com/…

- Walsh-Cotton, K. (2025, October 23). Aussie fashion brand owner faces mass online backlash for defending her refusal to stock plus sizes. Mail Online; Daily Mail. www.dailymail.co.uk/…

APA Style Citations