Celebrity’s and Influencer’s Impact Through Time

Despite fashion looking random on the surface, trends don’t just show up out of nowhere. They usually have a person attached to them, someone with a face, a name, and a following. For decades, it was mostly celebrities deciding what people thought was worth wearing. Now, influencers have jumped in too, and in some cases, they’ve completely overtaken traditional fame. Clothes move from red carpets or TikTok videos to stores and closets at a ridiculous speed, and that says a lot about culture, class, and the way consumerism works right now.

The idea of celebrity influence and the role of the “fashion icon” isn’t some brand-new invention either. Actors and musicians have been influencing style for over a century. Audrey Hepburn and Coco Chanel had their little black dresses, David Bowie turned androgyny into something mainstream. What’s different now is the way all of it gets delivered. Magazines used to control what people saw, picking and choosing which looks got attention. That middle step doesn’t exist anymore. Social media lets celebrities and influencers dump their closets straight onto millions of people in real time. Trends don’t trickle down slowly, they flood feeds, and a single look can sell out in less than a week.

Fashion icons have always carried cultural weight, but the faces of those icons have shifted with the times.

Princess Diana is the perfect example of an older “fashion icon.” Every outfit she wore turned into a worldwide talking point, whether it was a black gown covered in pearls or just bike shorts with a baggy sweatshirt. Her outfits weren’t just liked, they were studied and copied. What locked her in as an icon wasn’t just her position as royalty, but the way she broke away from what royalty was supposed to look like. She was seen as untouchable when it came to style.

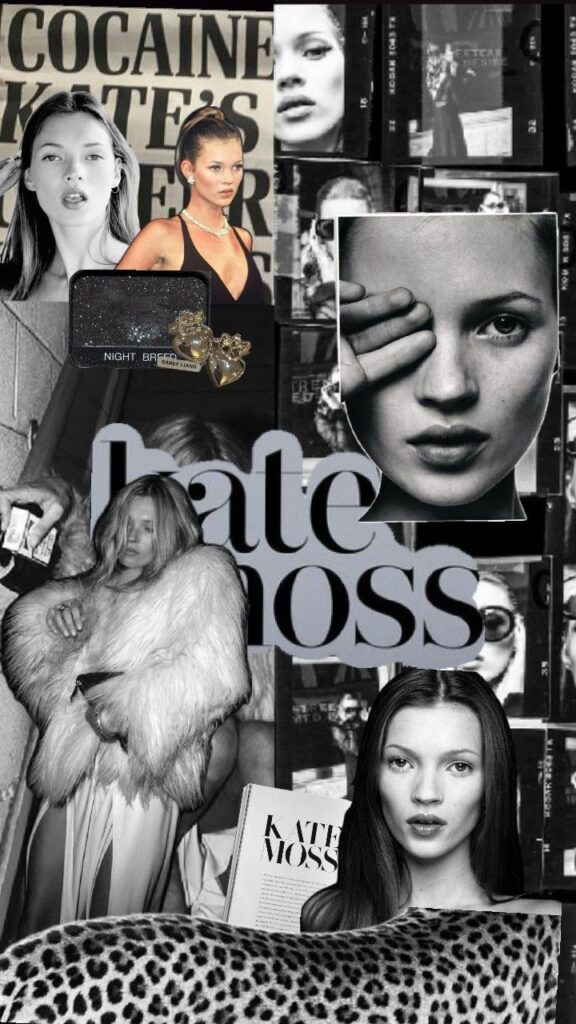

The 1990s moved things over to models like Kate Moss. She wasn’t a royal, but inside the fashion world she might as well have been. She defined an entire era with her aesthetic, and it’s still influencing style decades later. The “heroin chic” look, the slip dresses, and the barely-there styling gave her an edge that felt new and raw. If Diana’s influence was about grace and accessibility wrapped in royal glamour, Moss’s was about stripping it back and making imperfection fashionable. She proved that models could define cultural taste as much as designers could.

Celebrities still push fashion mainly through spectacle and access, moving the needle in three main ways. First, award shows, premieres, and photo shoots put aspirational looks in front of world wide audiences. They give people a place to build their own looks from, a style the public wants to emanate. From there, brand deals then turn that attention into sales, with stars fronting campaigns, signing contracts, and effectively selling their image to whatever brand pays the most, A-listers will wear borrowed couture, or sign on as ambassadors. These contracts let celebrities translate visibility into commerce. And some choose to simply cut out the middle step entirely and launch their own labels or collaborations, making their name the selling point. Celebrity fashion lines or creative director roles turn fame directly into a design voice, shaping not just what people buy but what they imagine as stylish. The appeal is straightforward: if a star with millions of followers attaches their image to a product, that product inherits the aura of their fame. Research and trend analytics tends to show that celebrity endorsements boost recognition and sales because fame itself carries credibility in the eye of the general public.

Influencers, on the other hand, tend to go about it differently. Instead of following in the aspirational distance most celebrities exhibit, their whole thing is relatability. A random “get ready with me” video filmed in a bedroom can sell out a mid-priced skirt faster than a celebrity magazine cover. People assume the influencer actually wears what they’re showing, so it feels more believable. Platforms eat this content up because it’s fast and low-budget, and it spreads like wildfire. Sometimes influencers with a fraction of the audience move more sales than traditional celebrities, just because they feel authentic. Brands know this and lean into it, since the results are quicker and cheaper than a full ad campaign.

Now, the spotlight doesn’t only belong to royals or models.

Influencers like Wisdom Kaye use platforms like Tiktok or Instagram, to build entire followings off experimental styling that gets pushed into millions of feeds with no magazine in between. Athletes like Lewis Hamilton now front campaigns and set trends, going so far as to be

the face of the 2025 Met Gala. Modern influencers and celebrities have moved into a style that challenges stereotypes about masculinity and fashion. The cultural “fashion crown” moves around in phases, from royalty, to supermodels, to digital creators and athletes, reflecting who society chooses to watch, follow, and imitate.

The success of celebrity and influencer marketing has never been an accident either. It’s just a mix of psychology and algorithms. A clever use of human nature and platform design. People are wired to follow whoever they think looks good, sounds believable, or seems similar to them. If that person is attached to a product, the product feels safer. Seeing a product associated with a star or trusted creator creates a shortcut in decision-making, with a lot of viewers and fans in these audiences falling into the thought process of “if it works for them, it must be good”. At the same time, algorithms reward anything that spreads fast, so an outfit that takes off gets thrown into millions of feeds. What used to take magazines months to establish can now blow up overnight.

The shift has broken down a lot of the old gatekeeping. Magazines and fashion houses no longer hold all the power. Thrifted fits, custom sneakers, and DIY projects can go viral just as easily as a designer’s runway collection. A kid painting jeans in their room can suddenly get noticed at the same scale as a luxury brand. The downside is that everything moves faster, so people end up buying cheap, disposable clothes that only last until the next microtrend arrives. The global hunt for the “next viral outfit” often results in piles of discarded fast fashion and the flattening of style across borders. Expression is everywhere, but originality can vanish under how quickly styles are copied. What looks like freedom of expression can quickly turn into uniformity, just sped up.

Examples of this happening aren’t hard to find either. The “

Kate Middleton effect” became shorthand for a phenomenon where essentially any and all outfits that were worn by the Duchess of Cambridge sold out within hours. The same thing happens today with influencers and celebrities posting outfits online. Whether that’s Bella Hadid’s streetwear, a thrifted jacket shown on YouTube, a TikTok video blowing up a random accessory. These moments don’t just sell products, they change how brands plan their entire stock. Labels will stockpile in anticipation of sudden viral hits or align product drops with influencer campaigns. Fashion retail has become a waiting game of who goes viral first.

This constant loop of fame and commerce obviously also comes with it's problems. Paid promotions aren’t always obvious. Products are pushed without disclosures, and people might not know if they’re watching someone’s real taste or an ad. The constant flood of micro-trends and uprising of “fast fashion” brands, like Shein, Forever21, and Cider, pumping out clothes designed to fall apart, encourages disposable shopping habits, selling clothes meant to last weeks rather than years. All the meanwhile, some celebrity-led brands might just slap a famous name on clothes that don’t even try to be good. But at the same time, the same system gives exposure to small designers and lets niche styles find a bigger audience. It’s exploitative and empowering at once, it simply depends on where the focus lands. Being shaped by these forces is unavoidable, but there’s a difference between using that influence and being entirely consumed by it. Dealing with all this influence isn’t about ignoring it. It’s about knowing how to use it without losing control. It's about recognising that trends can be adapted instead of copied. Take pieces of inspiration instead of swallowing whole outfits. Look at quality, not just hype. And, crucially, support those smaller creators and brands who prioritize sustainability over speed. Influence can drive discovery, but identity doesn’t need to be outsourced to a red carpet or TikTok scroll.

Celebrities and influencers don’t just sell clothes, they sell ways of being seen. Their power comes from the mirror they hold up to culture, sometimes flattering, sometimes distorted. That mirror reveals both the aspirations and insecurities of audiences, who either want to be close to fame or convinced by authenticity. Influence becomes empowering rather than extractive when creators, brands, and consumers commit to transparency, sustainability, and creativity. The future of fashion won’t be a single mirrored image everyone copies. Ideally it will be a collage of voices, each adapting and reinterpreting what they see into something that fits their life. Influence itself is inevitable, but what happens with it is a choice. Fashion doesn’t have to be a uniform reflection of celebrity closets, it can be a conversation, a remix, or even a rebellion.

- Allaire, C. (2020, July 5). Wisdom Kaye is the best-dressed guy on Tiktok. Vogue. www.vogue.com/...

- Dixon, N. (2024, September 18). How Kate Moss trends continue to influence fashion today | chic style collective. Chic Style Collective. www.chicstylecollective.com/kate-moss-trends/

- Hardy, A. (2024, April 24). Everything you need to know about fast fashion. Vogue. www.vogue.com/...

- Bryant, K. (2017, February 16). A comprehensive guide to the protest tees of new york fashion week. Vanity Fair. www.vanityfair.com/...

- Hinsliff, G. (2023, May 6). The “Kate effect”: How the princess of wales became the royals’ not-so-secret weapon. The Guardian. www.theguardian.com/...

- Gupta, C. (2025, March 24). Fashion As Resistance: When Clothing Becomes a Political Act. The Varsity. thevarsity.ca/...

- Jackson, H. (2025, May 6). Lewis Hamilton’s 2025 met Gala Look is loaded with symbolism-right down to the cuff links. Vogue. www.vogue.com/...

APA Style Citations